When Your Family Thinks Your Anxiety is “Demonic”: Navigating Religious Stigma and Mental Health

The invisible monster is real. You feel its claws in your chest, its whispers in your mind, the constant hum of dread it leaves in your wake. You try to describe it—the spiraling thoughts, the panic on the overpass, the dread that makes you hate living—but the people you love most see a different creature entirely. They see a spiritual failure, a moral weakness, a “demonic” influence. As one person shared, the wound cuts deepest when a parent attributes your suffering to “satan,” compounding the illness with a layer of isolating shame. You’re left fighting a war on two fronts: the internal battle with your own nervous system, and the external battle for your reality to be believed.

This article is for anyone who has been told their anxiety is “nonsense,” a lack of faith, or a sign of something sinister. It’s a guide to holding onto your truth when your support system misunderstands it, and building a path to healing that honors both your mental health and your journey.

The Unique Pain of Spiritual Misdiagnosis

When anxiety or depression is dismissed as a spiritual issue, it creates a specific and profound type of suffering. It’s not just a lack of understanding; it’s an invalidation that attacks the core of your experience. The problem is framed not as a medical condition, but as a character flaw or a spiritual battle you’re losing.

This narrative is devastatingly effective at breeding self-hatred. If your panic is “demonic,” then you must be inviting it in or too weak to cast it out. If your depression is “nonsense,” then your profound pain is just you being difficult. As one individual expressed, this leads to a terrible cycle: “I hate myself… my mom hates me.” The illness itself becomes a source of shame, making you feel broken and beyond hope within the very family structure that should offer sanctuary.

Why This Belief Persists

Understanding the “why” can sometimes help depersonalize the hurt. For many deeply religious families:

– Lack of Education: Mental health conditions are not understood as neurobiological.

– Cultural Framework: Suffering has historically been interpreted through a spiritual lens.

– Fear: The concept of a “chemical imbalance” or “genetic predisposition” can feel impersonal and frightening, whereas a spiritual cause offers a familiar, though flawed, framework for intervention (like prayer).

– Protective Instinct: Ironically, labeling it as “demonic” might be a misguided attempt to name a terrifying enemy they see hurting their loved one.

Recognizing these roots doesn’t excuse the harm, but it can help you see that their reaction is often about their limitations, not your worth.

Emotionally Separating Your Condition from Harmful Labels

The first and most crucial step in healing is to perform an internal surgery: to separate the reality of your anxiety from the harmful spiritual label slapped onto it. Your condition is valid, medical, and real. The stigma is a separate, external noise.

Reframing Your Self-Narrative

- Name It Correctly: Start using accurate, medical language for yourself, even silently. Instead of “I’m being attacked,” try “I’m experiencing a surge of anxiety due to my amygdala’s heightened threat response.” Clinical language can reclaim power.

- See the Evidence: Anxiety has tangible symptoms: rapid heart rate, shortness of breath, digestive issues, insomnia, muscle tension. These are physiological, not spiritual. As one person described the “invisible monster,” you may not be able to show an X-ray of anxiety, but you can point to its very real, physical footprints in your life.

- Practice Reality-Checking: When a family member says, “It’s just satan,” mentally counter with: “This is a documented medical condition that millions have. My brain is wired for high alert. This is not a choice or a spiritual failing.”

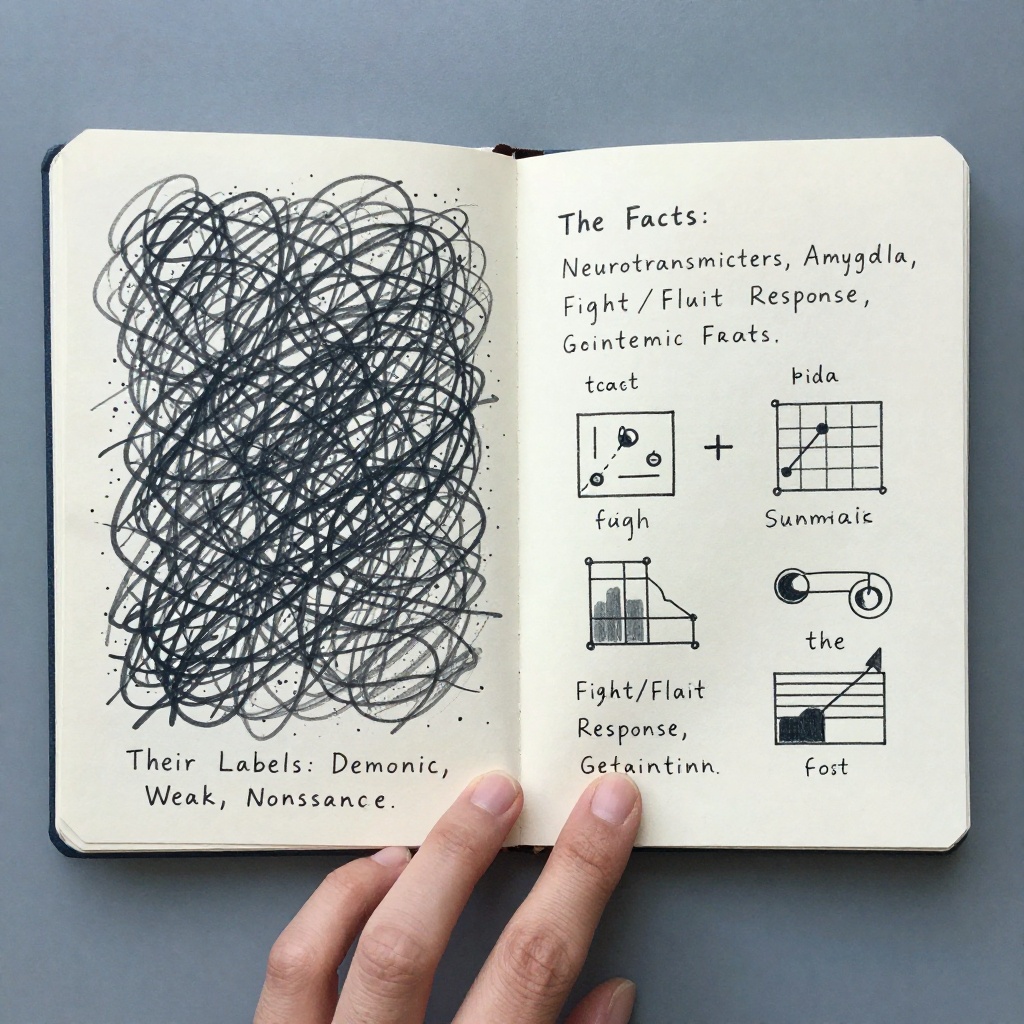

Actionable Takeaway: The Two-Truths Journal

Grab a notebook. Create two columns.

– Column A (Their Truth): Write down the painful things your family says. “You just need more faith.” “You’re letting the devil in.”

– Column B (Your Medical Truth): Next to each, write the biological or psychological fact. “Anxiety disorders involve serotonin and norepinephrine pathways.” “My panic attacks are a misfiring of the sympathetic nervous system.”

Visually seeing the separation on paper reinforces that their words belong to a column of opinion, not a column of fact about your body.

Scripts for Setting Boundaries with Unsupportive Family

You may not change their minds. The goal of setting boundaries is not to win a debate but to protect your well-being and create a space where you can heal. Boundaries are an act of self-compassion, not punishment.

How to Communicate Your Boundary

Use “I” statements to own your experience and needs without attacking their beliefs.

-

For Dismissive Comments:

“I understand you see this through a spiritual lens. I need you to understand that I am working with a doctor/therapist to manage a medical condition. When you call it ‘demonic,’ it interferes with my treatment and hurts me. I need you to respect my approach to getting better.” -

For Unsolicited Spiritual Advice:

“I appreciate that you want to help. Right now, the most supportive thing you can do is to [be specific: give me space, let me rest, not comment on my mood]. Please save the spiritual advice for another time.” -

For When You Need to Limit Contact:

“Our conversations about my mental health aren’t helpful for my recovery right now. I’m going to take a step back from discussing this topic. I still love you, and I hope we can talk about other things.”

Key Points for Enforcing Boundaries

- Be Consistent: If you say a topic is off-limits, calmly end the conversation or leave the room if it’s brought up.

- Release the Need for Agreement: You don’t need them to say, “You’re right, it’s medical.” You only need them to respect your rule for interaction.

- Prepare for Pushback: They may accuse you of being rebellious, faithless, or influenced. Have a simple, repeatable phrase ready: “This is what I need to get healthy.”

Finding Your Chosen Family and Validating Community

When your biological family cannot offer the support you need, you must become the architect of your own support system. Your “chosen family” consists of people who see you, believe you, and hold space for your reality without judgment.

Where to Look for Validation

- Therapy & Support Groups: This is your foundational chosen family. A therapist provides unconditional validation. Support groups (like the one mentioned in the examples that bans preaching to create a safe space) connect you with people who speak your language of struggle.

- Online Communities: Find moderated forums and subreddits focused on anxiety support. Look for communities with clear rules (like “NO preaching”) that prioritize evidence-based discussion.

- Friends Who Listen: Seek out friends who practice empathetic listening. As one person lamented, it often feels like “talking to a brick wall.” A true friend will say, “That sounds incredibly hard. I’m here.”

- Faith Communities That Get It (If Applicable): Some progressive religious or spiritual communities integrate modern mental health understanding. Seek out clergy or groups that speak about mental health with compassion and science.

How to Nurture These Connections

Be vulnerable about your search for understanding. You can say, “I’m dealing with anxiety, and I’m really needing people around me who can just listen without trying to fix it spiritually. Would you be willing to be that person for me sometimes?” This directly invites the kind of support you need.

The Essential Practice of Self-Compassion

When your external world fails to offer compassion, you must become its primary source for yourself. Self-compassion is not self-pity; it is the radical act of treating yourself with the same kindness you would offer a suffering friend.

Reframing Self-Talk

The self-hatred voiced in the examples (“I hate myself”) is a common symptom of both depression and the stigma itself. Actively rewrite that script.

– Instead of: “What is wrong with me?”

– Try: “I am really struggling right now. This is my anxiety, and it is incredibly difficult.”

– Instead of: “I’m sick in the head.”

– Try: “I have an illness in my brain, just like someone can have an illness in their heart. I am getting treatment for it.”

A Simple Self-Compassion Exercise

When you feel shame or panic rising:

1. Acknowledge: Place a hand on your heart. Say, “This is a moment of suffering.” (This is mindfulness.)

2. Common Humanity: Say, “Suffering is a part of life. I am not alone in this.” (This counters isolation.)

3. Kindness: Ask yourself, “What do I need to hear right now?” Then say it. “You are okay. You are safe. This feeling will pass. I am here with you.”

Holding Hope and Moving Forward

Navigating the gap between religious stigma and mental health reality is a lonely road, but you are not walking it alone. The very fact that you are seeking understanding—like the individuals who shared their stories of panic, desperation, and search for a preaching-free zone—is an act of profound courage.

Your healing journey is valid, whether it includes faith, science, or both. Your task is to protect that journey. It means building boundaries that may feel uncomfortable, seeking out those who can offer real support, and, most importantly, becoming the compassionate guardian of your own mind and heart.

The “invisible monster” is manageable with the right tools, community, and self-understanding. Don’t let anyone, no matter how well-intentioned, convince you to fight it with the wrong weapons, or worse, to believe you are the monster itself. Your experience is real. Your pain is valid. And your path to peace is yours to chart.

Your call to action today: Choose one step from this article. Bookmark a mental health support website. Write one boundary script in your notes app. Practice the self-compassion exercise once. Your healing is built one compassionate choice at a time.